Discussion and debate of mechanistic effects of manual therapy is a hot button topic. Osteopaths of the therapy world debate its use for correction of positional default, as others debate its neurophysiological effects being more evidence based within our current literature. Regardless your stance, it is interesting to discuss both sides of this fence. A healthy dose of skepticism within our treatments is needed. Sitting at a coffee shop on a Sunday afternoon seems like the right location to delve into pain science understanding of manual techniques and the science supporting the possible elaborate placebo called – manual therapy.

Where does this osteopathic skepticism come from? I am looking for provoking thought here, and understand literature doesn’t drive everything we do, but this should stem internal dialogue. Disclaimer that this is the external dialogue of one therapist and should not reflect all within the company.

Back to literature to drive thought, skepticism, and maybe some conflict. A few studies to evaluate specificity of our techniques have trickled down over the years. Tullberg et al demonstrated in 1998 with a roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of patients with the controversial diagnosis of: sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Here they examined twelve popular SIJ tests before and after an SIJ manipulation.4 Tests were deemed positive prior to manipulation and negative after, although according to the positional testing, no change was noted of the sacrum on the ilium after manual techniques were applied. Thus questioning sacroiliac joint dysfunction test validity for looking at positional default.4 Again in 2004, an investigation of manipulation’s specificity to an area was examined. The manipulation average error from the target segment was at least 2-6 segments away from target dependent on thoracic spine and lumbar spine.7 Consequently, the discussion stated that are finding in literature that we have a hard time selecting a diagnosis, and even if treated with manual therapy, we aren’t very specific in our treatments. Furthermore, this perpetuated Dr. Flynn’s work on clinical prediction rules to hopefully paint with a broader brush to select who is appropriate for manipulation.6 Fortunately, this was validated and thrown into clinicians tool box. Unfortunately though, this doesn’t seem like enough. We know manual therapy lends better outcomes in patient care than exercise alone, but why?

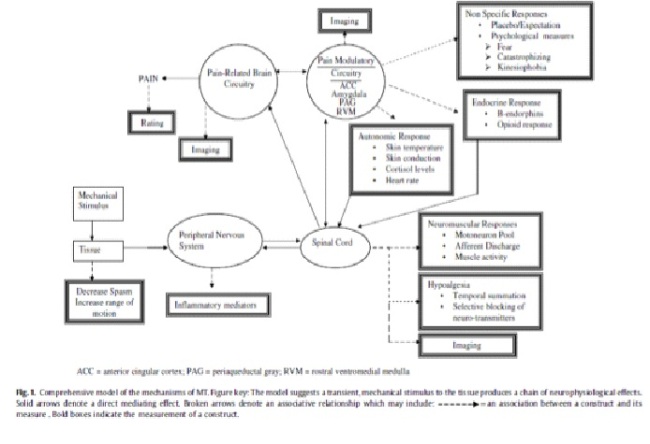

Numerous studies suggest manipulative therapy’s direct affect on central pain processing. Effects are suggested to have direct effect on relaxing hypertonic musculature, which can improve neuromuscular control and alter pain. Isolation of pain pathways are best identified in animal models. For example, Malisza et al found decreased activity dorsal horn of the spinal cord in rats following manual therapy at the knee. Indirect evidence demonstrates further effects including: afferent discharge, motoneuron pool excitability, muscle activity and temporal summation. These are all spinal cord mediated effects of manual therapy through afferent input. Discussion of indirect mechanisms are discussed in our heavy hitters of pain science literature: Dr. Biolosky, Dr. George and Dr. Bishop’s 2008 editorial on mechanisms of manual therapy – this is a good read – I advise taking a look. They recap our literature’s contribution of finding gating of nociception at the spinal cord due to stimulation of the mechanoreceptors and direct stimulation of a spinal reflex to alter muscle activity, or stimulation of pain centers in the brain.1,2,3

I tell patients that physical therapy, more specific manual therapy, can be seen as disruption of a cycle – this broad statement seems to keep me out of trouble. This idea that windup of pain can occur in human interaction with repetitive noxious stimulus is important to consider. Basically, patients feel pain once, the second stimulus is experienced to greater degree. To modify this cycle of central hyperalgesia or dorsal cell hyperexcitability is of interest to my practice patterns. If patients’ pain is our primary focus. Does it matter if we are approaching the goal of modulating symptoms from an osteopathic background or pain science, or maybe mixture of the two? It may not. We do know that we can tap into the nervous system and change theramal pain sensitivity through supraspinal pain pathways – so why not give it a shot – regardless your stance.

The following graph is a proposed model from Dr. Bialosky to understand mechanisms of manual therapy.1 For a clearer picture see reference 1. Here they break down pain a matrix of manual therapy from the left delving into mechanical stimulation, and the right discussing non specific responses and neuromuscular responses at supraspinal pathways to the spinal cord. The debate will be never ending in our field to rationale behind treatments. I do think that most can agree that the osteopathic model will be a thing of the past, especially as literature exposes its faults. I nearly cringe every time I hear someone say the scary word – alignment. Although, simplicity of touching a patient is a complex system and variability with patient to patient is nearly impossible to isolate in literature. I do hope to see our pain science literature grow in patient care to assist therapists and clinicians in how to manage pain to the best of our ability – even if we are elaborating on placebo.

Original post: December 2, 2013

References:

1) Bialosky, J. E., George, S. Z., & Bishop, M. D. (2008). How spinal manipulative therapy works: why ask why? The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 38(6), 293–5. doi:10.2519/jospt.2008.0118

2) Pickar JG, Wheeler JD. Response of muscle proprioceptors to spinal manipulative-like loads in the anesthetized cat. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:2-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/

3) Indahl A, Kaigle AM, Reikeras O, Holm SH. Interaction between the porcine lumbar intervertebral disc, zygapophysial joints, and paraspinal muscles. Spine. 1997;22:2834-2840.

4) Tullberg, T., Blomberg, S., Branth, B., & Johnsson, R. (1998). Manipulation Does Not Alter The Position of Sacroiliac Joint. SPINE.

5) Flynn, T., Fritz, J., Whitman, J., Wainner, R., Magel, J., Rendeiro, D., … Allison, S. (2002). A clinical prediction rule for classifying patients with low back pain who demonstrate short-term improvement with spinal manipulation. Spine, 27(24), 2835–43. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000035681.33747.8D

6) Pickar, J. G., & Bolton, P. S. (2012). Spinal manipulative therapy and somatosensory activation. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology : official journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology, 22(5), 785–94. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.01.015

7) Ross, J. K., Bereznick, D. E., & McGill, S. M. (2004). Determining cavitation location during lumbar and thoracic spinal manipulation: is spinal manipulation accurate and specific? Spine, 29(13), 1452–7. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15223938

8) Krisztina L. Malisza PhD1,*, Patrick W. Stroman PhD1, Allan Turner1, Lori Gregorash1, Tadeusz Foniok1, Anthony Wright PhD. Functional MRI of the rat lumbar spinal cord involving painful stimulation and the effect of peripheral joint mobilization. Journal of MRI. 21 JUL 2003. 159-163.

9) Dr. Joel Bialosky, PT, PhD. Evidence in Motion Lecture.